The Gulag Archipelago is a camp system that spans the entire country. The “natives” of this archipelago were people who went through arrest and the wrong court. People were arrested mainly at night, and half-dressed, confused, not understanding their guilt, they were thrown into the terrible meat grinder of the camps.

The history of the Archipelago began in 1917 with the "Red Terror" declared by Lenin. This event became the "source" from which the camps were filled with the "rivers" of innocently convicted. At first, only foreigners were imprisoned, but with the advent of Stalin's power, high-profile processes broke out: the case of doctors, engineers, food industry pests, clergy, and those responsible for Kirov's death. Behind high-profile processes hid many unspoken deeds replenishing the Archipelago. In addition, many "enemies of the people" were arrested, whole nationalities got into exile, and dispossessed peasants were exiled by villages. The war did not stop these flows, on the contrary, they intensified due to Russified Germans, rumors and people who were held captive or in the rear. After the war, emigrants and real traitors - the Vlasovites and the Cossacks of Krasnodar - joined them. The “natives” of the Archipelago also became those who filled it — the tops of the party and the NKVD were periodically thinning out.

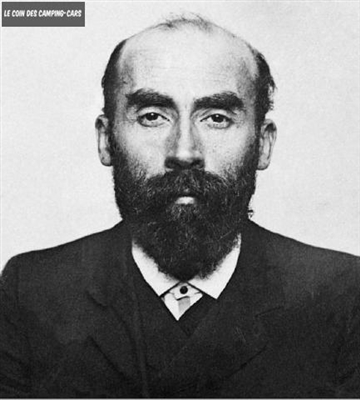

The basis of all the arrests was the Fifty-Eighth Article, consisting of fourteen paragraphs with sentences of 10, 15, 20 and 25 years. Ten years were given only to children. The purpose of the 58th investigation was not to prove guilt, but to break the will of man. For this, torture was widely used, which was limited only by the imagination of the investigator. Investigation protocols were drawn up so that the arrested person involuntarily pulled others along. Alexander Solzhenitsyn also went through such an investigation. In order not to harm others, he signed an indictment condemning him to ten years of imprisonment and eternal exile.

The very first punitive body was the Revolutionary Tribunal, created in 1918. Its members had the right to shoot "traitors" without trial. He turned into the Cheka, then the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, from which the NKVD was born. The executions did not last long. The death penalty was abolished in 1927 and was left only for the 58th. In 1947, Stalin replaced the “highest measure” with 25 years of camps - the country needed slaves.

The very first “island” of the Archipelago arose in 1923 on the site of the Solovetsky Monastery. Then came the TONs - special prisons and stages. People came to the Archipelago in many ways: in a train car, on barges, steamboats and on foot. The arrested were delivered to jails in “funnels” - black vans. The role of the ports of the Archipelago was played by shipments, temporary camps consisting of tents, dugouts, barracks or open-air plots of land. On all shipments, keeping “political” in check was helped by specially selected lessons, or “socially close”. Solzhenitsyn traveled to Krasnaya Presnya in 1945.

Emigrants, peasants and "small nations" transported in red trains. Most often, such trains stopped from scratch, in the middle of the steppe or taiga, and the convicts themselves built a camp. Particularly important prisoners, mostly scientists, were transported by special convoys. So Solzhenitsyn was transported. He called himself a nuclear physicist, and after Krasnaya Presnya he was transported to Butyrki.

The law on forced labor was adopted by Lenin in 1918. Since then, the “natives” of the Gulag have been used as free labor. Forced labor camps were merged into GUMZak (Main Directorate of Detention Places), and of which the Gulag (Main Directorate of Camps) was born. The most terrible places of the Archipelago were the ELEPHANTS - Northern Special Purpose Camps - which included the Solovki.

The prisoner became even more difficult after the introduction of five-year plans. Until 1930, only about 40% of “Aborigines” worked. The first five-year plan marked the beginning of the "great construction projects." Prisoners built highways, railways and canals with their bare hands, without equipment and money. People worked 12-14 hours a day, deprived of normal food and warm clothes. These construction sites claimed thousands of lives.

It could not do without escapes, but to run "into the void", not hoping for help, was almost impossible. The population living outside the camps practically did not know what was going on behind the barbed wire. Many sincerely believed that the "political" were actually guilty. In addition, they paid well for the capture of those who escaped from the camp.

By 1937, the archipelago had grown throughout the country. Camps for the 38th appeared in Siberia, the Far East and Central Asia. Each camp was run by two chiefs: one led production, the other manpower. The main way of influencing the “natives” was the “pot” - the distribution of soldering according to the norm. When the Kotlovka ceased to help, brigades were created. For failure to comply with the plan, the foreman was put in a punishment cell. Solzhenitsyn fully experienced all this in the New Jerusalem camp, where he ended up on August 14, 1945.

The life of the "native" consisted of hunger, cold and endless work. The main work for the prisoners was felling, which during the years of the war was called "dry execution." The prisoners lived in tents or dugouts, where it was impossible to dry wet clothes. These homes were often searched, and people were suddenly transferred to other jobs. In such conditions, prisoners very quickly turned into "goners." The camp medical unit practically did not participate in the life of prisoners. So, in the Burepolomsky camp in February, 12 people died every night, and their things again went into business.

Women prisoners endured the prison easier than men, and in the camps they died faster. The camp bosses and “morons” took the most beautiful, the rest went to general work. If a woman became pregnant, she was sent to a special camp. The mother, who had finished breastfeeding, went back to the camp, and the child went to the orphanage. In 1946, women's camps were created, and the women's forest felling was canceled. Sat in the camps and "youngsters", children under 12 years old. Separate colonies also existed for them. Another "character" of the camps was the camp "moron", a man who managed to get light work and a warm, well-fed place. Basically, they survived.

By 1950, the camps were filled with "enemies of the people." Among them were real political figures who even went on strike in the Archipelago, unfortunately to no avail - they were not supported by public opinion. The Soviet people did not know anything at all, and the Gulag stood on it. Some prisoners, however, remained faithful to the party and Stalin to the last. It was from such orthodox people that informers or sexots were obtained — the eyes and ears of the Cheka-KGB. They also tried to recruit Solzhenitsyn. He signed a commitment, but did not engage in denunciation.

A person who has lived to the end of the term rarely got into freedom. Most often, he became a "repeater." The prisoners could only escape. Caught fugitives were punished. The 1933 Correctional Labor Code, which was in force until the early 1960s, prohibited detention centers. By this time, other types of intra-camp punishments had been invented: RURs (Company of the Enhanced Mode), BURy (Brigades of the Enhanced Mode), ZURy (Zone of the Enhanced Mode) and ShIZo (Penal Isolators).

Each camp zone was certainly surrounded by a village. Many villages over time turned into large cities, such as Magadan or Norilsk. The on-camp world was inhabited by the families of officers and warders, the adolescence, and many different adventurers and crooks. Despite the free labor camp, the camps cost the state a lot.In 1931, the Archipelago was transferred to self-sufficiency, but nothing came of it, since the guards had to pay, and the camp leaders to steal.

Stalin did not stop at the camps. On April 17, 1943, he introduced penal servitude and the gallows. Hard labor camps were created at the mines, and this was the most terrible work. Women were also condemned to hard labor. Basically, traitors became convicts: policemen, burgomaster, "German bedding", but before they were also Soviet people. The difference between camp and hard labor began to disappear by 1946. In 1948, a certain alloy of camp and hard labor was created - Special Camps. All 58th sat in them. Prisoners were called by numbers and given the hardest work. Solzhenitsyn went to a special camp of Stepnoy, then - Ekibastuz.

The uprisings and strikes of prisoners also took place in special camps. The very first rebellion took place in a camp near Ust-Usa in the winter of 1942. The excitement arose because only "political" were gathered in special camps. Solzhenitsyn himself also participated in the 1952 strike.

Each "native" of the Archipelago after the end of the term was waiting for a link. Until 1930, this was a “minus”: the liberated one could choose a place of residence, with the exception of some cities. After 1930, exile became a separate type of isolation, and since 1948 it became a layer between the zone and the rest of the world. Every exile could at any moment be back in the camp. Some were immediately given a term in the form of exile - mainly dispossessed peasants and small nations. Solzhenitsyn was finishing his term in the Kok-Tereksky district of Kazakhstan. Link from the 58th began to be removed only after the XX Congress. Liberation was also difficult to survive. The man changed, became a stranger to his loved ones, and had to hide his past from friends and colleagues.

The history of the Special Camps continued after the death of Stalin. In 1954, they merged with the ITL, but did not disappear. After his release, Solzhenitsyn began to receive letters from modern “natives” of the Archipelago who convinced him that the Gulag would exist as long as the system that created it existed.

Perfume mail

Perfume mail