Alvaro Mendiola, a Spanish journalist and film director who has long been living in France in voluntary exile, suffered a severe heart attack, after which the doctors prescribed him peace, and his wife Dolores comes to Spain. Under the canopy of his family home, which once belonged to a large family, of which he was the only one left, Alvaro recounts his whole life, his family history, the history of Spain. The past and present interfere in his mind, forming a kaleidoscopic picture of people and events; the outlines of family history, inextricably linked with the history of the country, are gradually emerging.

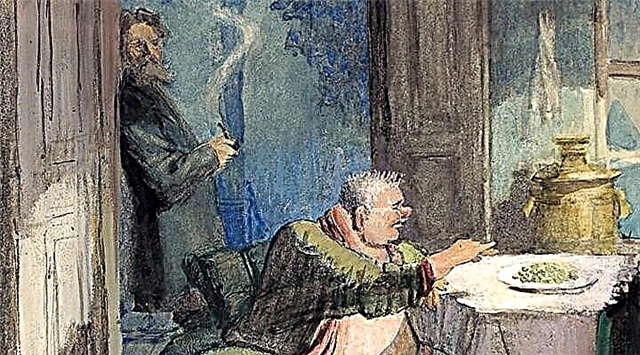

At one time, the richest Mendiola family owned vast plantations in Cuba, a sugar processing plant and many black slaves - all this was the basis of the welfare of the clan that flourished at that time. The hero’s great-grandfather, a poor Asturian hidalgo, once left for America, hoping to make a fortune, and quite succeeded. However, the story of the family goes on descending: the children inherited a huge fortune, but not the talents and the capacity for work of the father. The sugar factory had to be sold, and after Spain lost the last colonies in 1898, the family broke up. Grandfather Alvaro settled in the suburbs of Barcelona, where he bought a big house and lived in a big way: in addition to the town house, the family had an estate near Barcelona and an ancestral house in Yesta. Alvaro recalls all this while looking at an album with family photos. People who have been dead for a long time are looking at him: one died in the civil war, the other committed suicide on the shores of Lake Geneva, someone just died.

Flipping through the album, Alvaro recalls his childhood, the devout senorita Lourdes, the governess who read him a book about infant martyrs; recalls how soon after the victory of the Popular Front, when churches were burned all over Spain, an exalted governess tried to enter the burning church with him in order to suffer for faith, and the militianos was stopped. Варlvaro recalls how hostile the new authorities were in the house, how his father left for Yesta, and soon news came from there that he was shot by a militianos; how in the end the family fled to a resort town in the south of France and there they waited for the victory of the Franco, eagerly catching news from the fronts.

Having matured, Alvaro parted with his relatives - with those who still survived: all his sympathies are on the side of the Republicans. Actually, reflections on the events of 1936-1939, about how they affected the face of Spain in the mid-sixties, when Alvaro returns to his homeland, pass through the whole book with a red thread. He left his homeland a long time ago after his documentary was met with hostility, where he tried to show not a tourist paradise, in which the regime tried to turn the country, but another Spain - Spain hungry and destitute. After this film, he became a pariah among compatriots and chose to live in France.

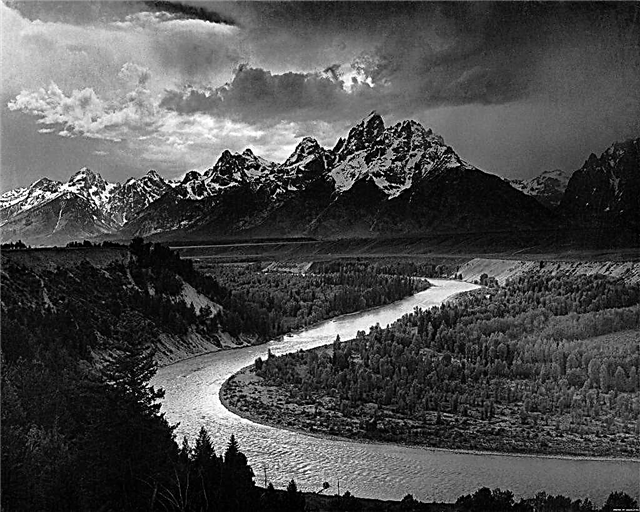

Now, looking back at his childhood, at close people, Alvaro sees and evaluates them through the prism of his current views. Warm attitude towards relatives is connected with the understanding that they were all a historical anachronism, that they managed to live without noticing the changes taking place around, for which fate punished them. The distant years of the civil war are approaching almost right up when Alvaro goes to Yest to look at the place where his father died. The hero hardly remembers his father, and this torments him. Standing at the cross that was preserved at the scene of the shooting and looking at the landscape, which has hardly changed over the years, Alvaro is trying to imagine what this person should have felt. The shooting of Alvaro's father, and with him several more people, was a kind of act of revenge: some time before the government brutally cracked down on these places peasants who opposed the will of the authorities. One of the few surviving eyewitnesses of this long-standing tragedy tells about the atrocities and cruelty of Alvaro. Listening to this peasant, Alvaro thinks that there is no and could not be right or guilty in that war, as there are no losers and winners, there is only losing Spain.

So, in constant memories Alvaro spends a month in Spain. The years that he lived away from her, intoxicated by freedom, now seem to him empty - he did not learn the responsibility that many of his friends who remained in the country gained. This sense of responsibility is given through severe trials, such as, for example, that fell to the lot of Antonio, a friend of Alvaro, with whom they shot a documentary that caused so many attacks. Antonio was arrested, spent eighteen months in prison, and then deported to his native land, where he was to live under the constant supervision of the police. The regional police department monitored his every move and kept notes in a special diary, a copy of which lawyer Antonio received after the trial — this diary is abundantly cited in the book. Alvaro recalls what he was doing at that time. His integration into a new, Parisian life was also difficult: compulsory participation in meetings of various republican groups so as not to break ties with Spanish emigration, and participation in events of the left French intelligentsia, for which, after the story with the film, he was the object of charity. Alvaro recalls his meeting with Dolores, the beginning of their love, his trip to Cuba, the friends with whom he participated in the anti-French student movement.

All his attempts to connect the past and the present pursue only one goal - to regain their homeland, a sense of unity with it. Alvaro very painfully perceives the changes that have taken place in the country, the ease with which the most acute problems were covered with a cardboard facade of prosperity in order to attract tourists, and the ease with which the people of Spain reconciled to this. At the end of his stay in Spain - and at the end of the novel - Alvaro travels to Mount Montjuic in Barcelona, where the President of the Generalitat, Government of Catalonia, Luis Kompanis was shot. And not far from this place, where, of course, there is no monument, he sees a group of tourists whom the guide tells that here during the Civil War, the Reds shot priests and senior officers, so a monument to the fallen was erected here. Alvaro does not pay attention to the usual official interpretation of the national tragedy, he has long been accustomed to this. He is struck by the fact that tourists take pictures against the backdrop of the monument, asking each other what kind of war the guide spoke about. And looking from the heights of Montjuic to Barcelona below, Alvaro thinks that the victory of the regime is not a victory, that the life of the people still goes on its own and that he must try to capture truthfully what he witnessed. This is the internal result of his trip to his homeland.